Modern Standard Arabic

| Modern Standard Arabic | ||

|---|---|---|

| Spoken in | ||

| Total speakers | ca. 300 million; up to 1 billion (mainly Muslims around the globe) with a significant or working knowledge of the language. | |

| Language family | Afro-Asiatic | |

| Writing system | Arabic alphabet | |

| Official status | ||

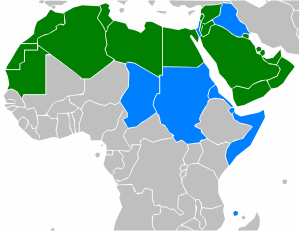

| Official language in | Arab world, Israel, Djibouti, Eritrea, Chad, Somalia, Comoros | |

| Regulated by | modelled after the Qur'an; Academy of the Arabic Language | |

| Language codes | ||

| ISO 639-1 | ar | |

| ISO 639-2 | ara | |

| ISO 639-3 | arb | |

| Linguasphere | ||

| Note: This page may contain IPA phonetic symbols in Unicode. | ||

Modern Standard Arabic (MSA; Arabic: اللغة العربية الفصحى al-luġatu l-ʿarabīyatu l-fuṣḥā "the most eloquent Arabic language"), Standard Arabic, or Literary Arabic is the standard and literary variety of Arabic used in writing and in formal speech. It is part of the Arabic macrolanguage.

Most western scholars distinguish two standard (al-)fuṣ-ḥā (الفصحى) varieties of the Arabic language: the Classical Arabic (CA) (اللغة العربية التراثية) of the Qur'an and early Islamic (7th to 9th centuries) literature, and Modern Standard Arabic (MSA) (اللغة العربية المعيارية الحديثة), the standard language in use today. The modern standard language is based on the Classical language. Most Arabs consider the two varieties to be two registers of one language, although the two registers can be described in Arabic as فصحى العصر fuṣḥā al-ʻaṣr (MSA) and فصحى التراث fuṣḥā at-turāth (CA).[1]

Contents |

Classical Arabic

Classical Arabic, also known as Qur'anic Arabic, is the language used in the Qur'an as well as in numerous literary texts from Umayyad and Abbasid times (7th to 9th centuries).

Classical Arabic is often considered to be the parent language of all the spoken varieties of Arabic, but recent scholarship, such as Clive Holes' (2004), shades this view, showing that other Ancient North Arabian dialects were extant in the 7th century and may be the origin of current spoken varieties.

Modern Standard Arabic

- See also Arabic phonology

Modern Standard Arabic (MSA) is the literary standard across the Middle East and North Africa, and one of the official six languages of the United Nations. Most printed matter in the Arab World—including most books, newspapers, magazines, official documents, and reading primers for small children—is written in MSA. "Colloquial" Arabic refers to the many national or regional varieties derived from Arabic spoken daily across the region and learned as a first language. They are not typically written, although a certain amount of literature (particularly plays and poetry) exists in many of them. Literary Arabic is the official language of all Arab countries and is the only form of Arabic taught in schools at all stages.

The sociolinguistic situation of Arabic in modern times provides a prime example of the linguistic phenomenon of diglossia – the use of two distinct varieties of the same language, usually in different social contexts. Educated Arabic-speakers are usually able to communicate in MSA in formal situations across national boundaries – thus, MSA is a classic example of a Dachsprache. This diglossic situation facilitates code-switching in which a speaker switches back and forth between the two varieties of the language, sometimes even within the same sentence. In instances in which highly educated Arabic-speakers of different nationalities engage in conversation but find their dialects mutually unintelligible (e.g. a Moroccan speaking with a Lebanese), they are able to code switch into MSA for the sake of communication.

Although closely based on Classical Arabic (especially from the pre-Islamic to the Abbasid period, including Qur'anic Arabic), literary Arabic continues to evolve. Classical Arabic is considered normative; modern authors attempt (with varying degrees of success) to follow the syntactic and grammatical norms laid down by Classical grammarians (such as Sibawayh), and to use the vocabulary defined in Classical dictionaries (such as the Lisan al-Arab.)

Switch from Classical Arabic to MSA

In spite of the romantic and variously successful attempts of modern Arab authors to follow the syntactic and grammatical norms of Classical Arabic, the exigencies of modernity have led to the adoption of numerous terms which would have been mysterious to a Classical author, whether taken from other languages (e.g. فيلم film) or coined from existing lexical resources (e.g. هاتف hātif "telephone" < "caller").

Structural influence from foreign languages or from the vernaculars has also affected Modern Standard Arabic: for example, MSA texts sometimes use the format "X, X, X, and X" when listing things, whereas Classical Arabic prefers "X and X and X and X", and subject-initial sentences may be more common in MSA than in Classical Arabic.[2]

For all these reasons, Modern Standard Arabic is generally treated as a separate language in non-Arab sources. Arab sources generally tend to regard MSA and Classical Arabic as different registers of one and the same language. Speakers of Modern Standard Arabic do not always observe the intricate rules of Classical Arabic grammar. Modern Standard Arabic principally differs from Classical Arabic in three areas: lexicon, stylistics, and certain innovations on the periphery that are not strictly regulated by the classical authorities. On the whole, Modern Standard Arabic is not homogeneous; there are authors who write in a style very close to the classical models and others who try to create new stylistic patterns. Add to this regional differences in vocabulary depending upon the influence of the local Arabic varieties and the influences of foreign languages, such as French in North Africa or English in Egypt, Jordan, and other countries.[3]

Reading out loud in MSA for various reasons is becoming increasingly simpler, using less strict rules compared to CA, notably the inflection or i`rāb is often omitted making it closer to spoken varieties of Arabic. It depends on the speaker's knowledge and attitude to the grammar of the Classical Arabic, as well as the region and the intended audience.

Pronunciation of foreign names in MSA can be sometimes inconsistent, names can be pronounced or even spelled differently in different regions and by different speakers. Generally, foreign geographical or personal names don't have case endings. There may be sounds used, which are missing in the Classical Arabic but they may exist in colloquial varieties - consonants - "v", "p", "g", "ch" ([t͡ʃ]), "zh" (French "j": [ʒ]), these consonants may or may not be written with special letters; and vowels - "o", "e" (both short and long), there are no special letters in Arabic to distinguish between e/i and o/u pairs but the sounds o and e (short and long) exist in the colloquial varieties of Arabic and some foreign words in MSA.

Regional variants

MSA is used uniformly across the Middle East, but some regional variations exist due to influence from the spoken vernaculars. People who "speak" MSA during interviews often give away their national or ethnic origins by their pronunciation of certain phonemes (e.g. the realization of the Classical jīm ج (/dʒ/) as [ɡ] by Egyptians, and as [ʒ] by Lebanese), and by mixing between vernacular and Classical words and forms. Classical/vernacular mixing in formal writing can also be found (e.g. in some Egyptian newspaper editorials).

Formal Spoken Arabic

Formal Spoken Arabic is a new Western term used to describe Arabic spoken by educated native speakers in a formal situation or when communicating with Arabs from other Arab countries. It represents a grammatically simplified version of Modern Standard Arabic with some elements of colloquial dialects.[4] Other similar terms are: Educated Spoken Arabic, Inter-Arabic, Middle Arabic and Spoken MSA. In Arabic this term can be described as عامية المثقفين ʻāmmiyat al-'muthaqqafīn.[1]

Grammar

Common phrases

| Translation | Phrase | IPA | Romanization (ALA-LC) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Arabic | العربية | /alʕaraˈbijːa(h)/ | al-‘arabiyyah |

| hello/welcome | مرحبًا | /ˈmarħaban/ | marḥaban |

| peace | سلام | /saˈlaːm/ | salām |

| how are you?(m) | كيف حالك؟ | /kajfa ħaːluk/ | kayfa ḥāluk |

| see you | إلى اللقاء | /ʔilalliˈqaʔ/ | ilā lliqā’ |

| goodbye | مع السلامة | /maʕa ssaˈlaːma/ | ma‘a as-salāmah |

| please | من فضلك | /min ˈfadˁlak/ (to male); /min ˈfadˁlik/ (to female) | min faḍlik |

| thanks | شكرًا | /ˈʃukran/ | shukran |

| that one | ذٰلك | /ˈðaːlika/ | dhālika |

| How much/How many? | كم؟ | /kam/ | kam? |

| English | الإنكليزية | /alʔinɡliˈziːja/ | al-inglīzīyah |

| What is your name? | ما اسمك؟ | /ˈmaː ʔismuk/ | mā ismuk |

| I don’t know | لا أعرف | /laː ˈʔaʕrifu/ | lā a‘rif |

Notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Alaa Elgibali and El-Said M. Badawi. Understanding Arabic: Essays in Contemporary Arabic Linguistics in Honor of El-Said M. Badawi, 1996. Page 105.

- ↑ Alan S. Kaye (1991). "The Hamzat al-Waṣl in Contemporary Modern Standard Arabic". Journal of the American Oriental Society (American Oriental Society) 111 (3): 572–574. doi:10.2307/604273. http://www.jstor.org/stable/604273.

- ↑ Wolfdietrich Fischer. 1997. "Classical Arabic," The Semitic Languages. London: Routledge. Pg 189.

- ↑ Abed, Shukri B. (2006). Focus on Contemporary Arabic (Conversations with Native Speakers). Yale University Press. ISBN 0300109482.

See also

- Arabic language

- Varieties of Arabic

- Arabic literature

- Dictionary of Modern Written Arabic

- Arabic English Lexicon

- Arabic Diglossia

- Arabic phonology

References

- Ethnologue entry for Standard Arabic

- Holes, Clive (2004) Modern Arabic: Structures, Functions, and Varieties Georgetown University Press. ISBN 1-58901-022-1

External links

- Classical Arabic Blog

- Arabic Gems Learn about Arabic linguistics and morphology.

- Online Classical Arabic Reader

- Learn Arabic WikiBook

- Yamli Editor - The Smart Arabic Keyboard (with automatic conversions and dictionary for better selections)

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||